contributed by Crystal Davidson

Sneakily slithering, seeking sustenance, single celled slime molds slowly slide through the forest…

It takes a keen eye, and a good amount of moisture to catch a myxomycete! These tiny friends of fungi are often found on dead wood, but can sometimes even be seen creeping across your lawn.

The first myxo that ever caught my attention was Arcyria denudata, which I first saw in a field guide. I immediately loved the common name “Cotton Candy Slime Mold”. Getting to meet one in real life, however, was even more thrilling, as the tiny pinkish red fruit bodies really do evoke memories of the fluffy fair food! One of the most prolific slimes in our area is Fuligo septica, which has the stomach-churning common name of ‘dog vomit slime mold’. Since I’m not a dog owner, I can’t speculate as to the visual accuracy of this name, but I’d guess it exists for a reason. You’ll often find it creeping through a flower bed in urban areas, though it can be found in the wild as well.

There are also many species of Trichia, Hemitrichia, and Metatrichia that frequent Ohio. Careful examination of the subtle features of the fruiting bodies can sometimes aid in distinguishing them. For instance, this specimen is most likely Hemitrichia clavata, which looks very similar to, but has a more elongated cup at the base than H. calyculata.

Another common myxomycete is Physarum polycephalum. “Polycephalum” means “many headed”, and the fruiting stage makes it clear from whence this name came. In the plasmodial stage, P. polycephalum can be difficult to distinguish from Badhamia utricularis and other myxos, but most slimes can’t be identified solely from this stage. Once they fruit, however, the differences are obvious. P. polycephalum usually fruits upwards, away from gravitational forces, whereas B. utricularis typically hangs down.

A fun thing to do with myxomycetes is to capture them and bring them home to start your very own personal slimarium! To create one, you’ll need an enclosed container to keep in both your slime and any unexpected visitors that may sneak home with you. An old fish tank with a bit of plastic wrap over the top worked quite well for me, although any clear enclosure will suffice. I added some large rocks, well decayed pieces of log, a few handfuls of live moss, a bit of water at the bottom, and I periodically misted inside to maintain humidity. When you’ve found a specimen, simply remove a small bit of the substrate along with the myxomycete, and carefully transport it back to the tank. In a pinch, you can even use a clear plastic food container with a moist paper towel at the bottom as a living area.

While slime molds love oats, and they are a consistently consumed food source, I’ve found it to be more interesting to offer them a variety of foods and see what they prefer! They typically love mushrooms, though they have strong preferences on which they will eat. Pleurotus spp. are always a favorite, Postia sp. was not a big hit, they only eat the bacteria off the surface of the Trametes versicolor, and they absolutely abhor Rhodotus palmatus. Additionally, they will eat pasta and the bacteria on the outside of acorns, but despise raspberries and broccoli. This is an example of how slime molds navigate to make choices and select food source.

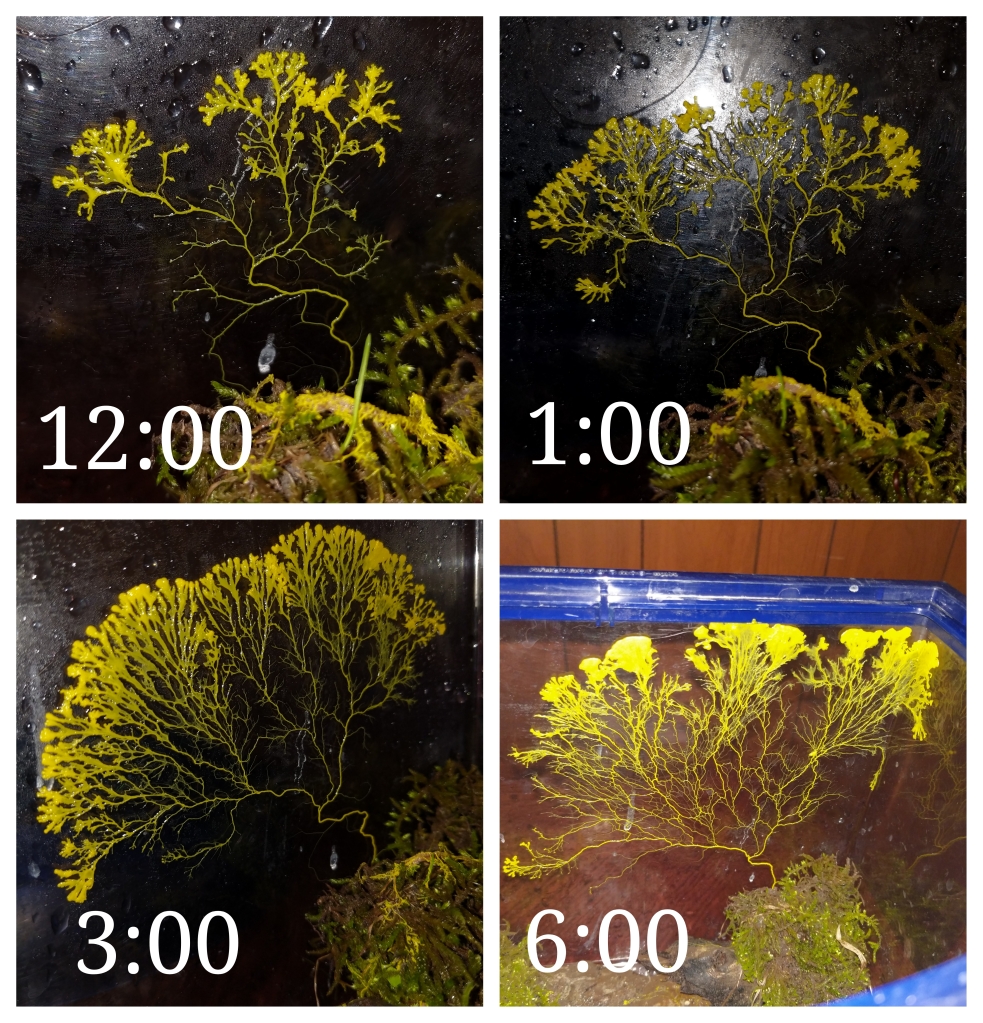

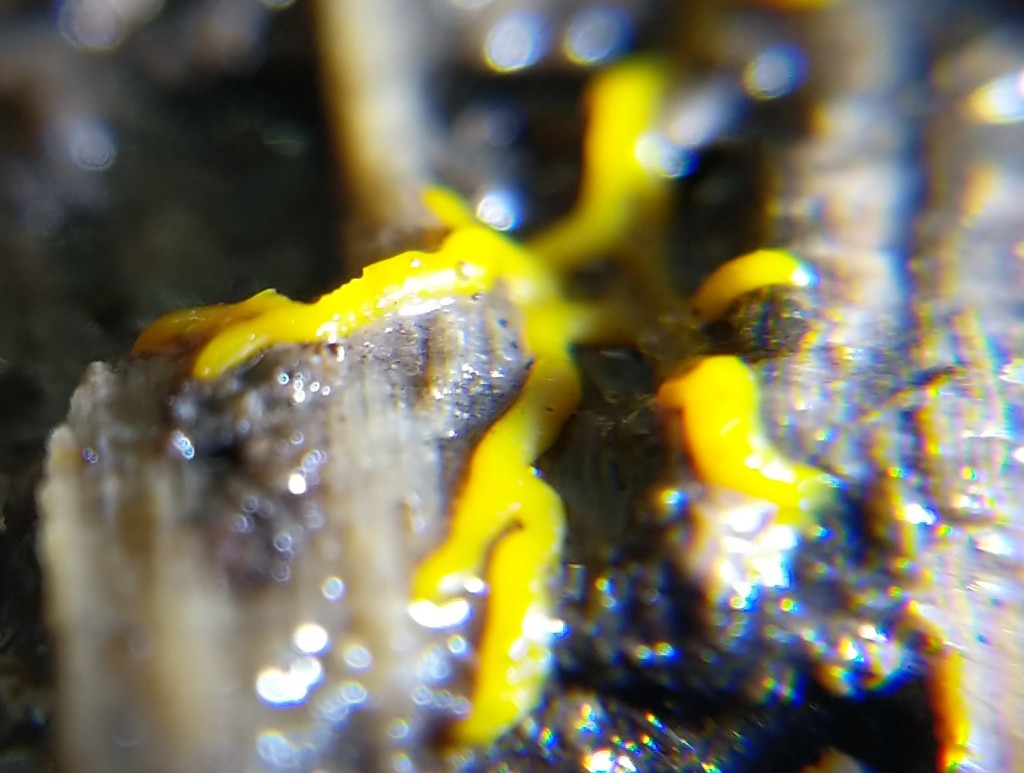

If you’re wondering how this blob-like organism moves, it does so through a pulsing locomotion. The slime forms “veins” which are wrapped in proteins that squeeze, creating a wave like effect. The waves move forward and recede slightly less with each pulse through the finger-line extensions known as pseudopods. You can see the progress over time here, as well as the ripples of the waves in the second photo.

Since I was eager to find out exactly what my most recent slime pet was, I forced it to fruit by denying it food. Despite the fact that myxomycetes can perceive light and typically avoid it, when they are ready to fruit, they will sometimes climb up to a high point, which may help to increase the range of the spore dispersal. I was quite pleased to discover upon fruiting, that this specimen was in fact Physarum polycephalum, which is often used in lab studies, including the semi-famous study of slime molds solving mazes.

Now you might have thought this story was over at the fruiting, and I did too! Imagine my surprise when after a few months of not introducing anything new into the slimarium, a second slime suddenly appeared! Remember, they are sneaky! In the plasmodial stage, this Arcyria cinerea doesn’t look much different than its roommate, P. polycephalum. Once it fruited, however, the differences were obvious.

It is also interesting to note that there are some fungi that feed off of slime molds. I only discovered this Polycephalomyces tomentosus feeding on this Hemitrichia calyculata once I got home and was editing my photos. Next time, I’ll try to be more observant of the even tinier things.

To learn more about these fascinating life forms, consider also joining the Facebook group Slime Mold Identification & Appreciation, which was even mentioned in the recent NOVA special on PBS, “Secret Mind of Slime”.

What a fun article on a non-fungus! Crystal, you are the Queen of alliteration! So cool that you’re engaging in baseline research 😀